ENGLISH VERSION DN DEBATT 7/10. The hype of AI may lead to an over-confidence in AI solutions, and will make us use unintelligent AI for tasks that require considerably more advanced intelligence, such as ability to understand, reason, and make moral judgements. A wise usage of AI should be governed by an awareness of the systems’ limitations, writes Thomas Hellström, Professor in Computing Science.

En utskrift från Dagens Nyheter, 2024-04-20 09:06

Artikelns ursprungsadress: https://www.dn.se/debatt/dangerous-over-confidence-in-ai-that-so-far-is-too-unintelligent/

Få ut mer av DN som inloggad

Du vet väl att du kan skapa ett gratiskonto på DN? Som inloggad kan du ta del av flera smarta funktioner.

- Följ dina intressen

- Nyhetsbrev

Almost daily we read about new fantastic break-throughs in artificial intelligence (AI). Large resources are invested in both research and development of AI solutions for practical problems in a range of areas in society. But there is an associated risk that AI is used for tasks that require much more intelligent machines than we currently have, primarily due to two factors:

1.

First of all, there is no real artificial intelligence. Not now and not on the visible research horizon. There has certainly been great progress in AI applications over the past decade. Working systems exist for voice recognition, translation, and in search engines, and prototypes of self-driving cars and service robots are being tested at several places around the world. But this is still far away from human-level intelligence, and from something that can be called sentient machines.

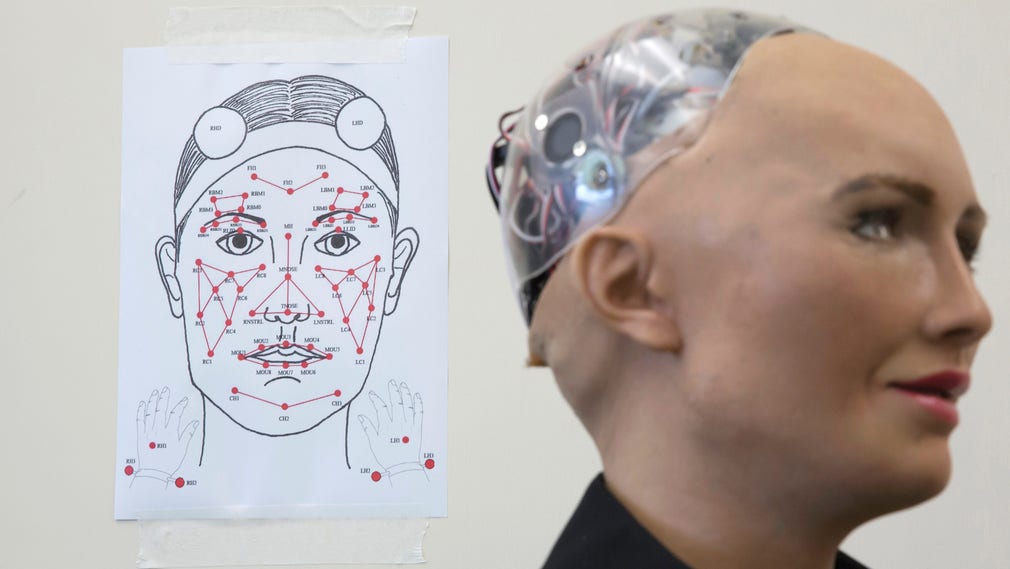

A self-driving car that works well in California would immediately drive off the road, if it would even start, in a Swedish snowstorm. And when the robot Erica, with an expressive face and voice, says she’s not afraid of death, she only repeats what her creator, Professor Ishiguro, has literally programmed into her computer. If she would say she’s afraid, there is also no reason to take that seriously, or try to comfort her.

2.

Second, academia, business, and media tend to exaggerate the intelligence of existing AI systems. We researchers often say that our robots “understand”, “feel”, and “decide”, not least when we describe what will be achieved with renewed research funding (btw, the robot Erica is not a “she” but an “it”, like all other machines). Also, companies tend to describe their robots and AI systems as equipped with close to human intelligence and emotions. Probably with the intention of selling as many products as possible.

Media in turn is often unquestioning rather than scrutinizing in its news reporting on AI. The reason for these tendencies to exaggerate AI is not necessarily a wish to deceive. The vision of creating artificial life and intelligence is deeply culturally anchored in us humans, and affects the way we interpret and describe what we do and see around us. We love to imagine intelligent machines, and the love rubs off on decision makers who pump billions into both research and entrepreneurship.

All in all, exaggerations may lead to over-confidence, which in combination with the pretty unintelligent AI we currently have, becomes a danger we should be more aware about. Namely that, the hype of AI may lead to an over-confidence in AI solutions, and will make us use unintelligent AI for tasks that require considerably more advanced intelligence, such as the ability to understand, reason, and make moral judgements.

● One example is banking systems for automatic assessment of loan applications. Such systems analyze huge amounts of old applications, and then try to imitate the human case handler’s assessments. Unfortunately, it turns out that such systems can become prejudiced and, for example, consistently discriminate applicants due to skin color or gender. The same problem appears in AI-based systems for automatic assessment of applications for jobs or participation in beauty contests.

● Another example is the AI-based image analysis systems used in driverless cars to detect the road, other vehicles, and pedestrians. The systems usually work excellently but have severe constraints that are revealed in a particular type of stress test. By adding noise to a camera image, you can fool the image analysis system to deliver breathtakingly incorrect analyzes of what’s in front of the camera. However, a human has no trouble seeing that the noisy image has exactly the same content as the unmodified image. These types of tests raise questions about whether the AI-based systems really understand images, or if they only learn that some formations of pixels should be called “car” or “pedestrian”.

The problem of over-confidence in AI may paradoxically increase rather than decrease over time. Already, computer programs can translate between, for example, Chinese and English. Quite well actually, but they sometimes make mistakes that no human would ever do. These computer programs will become better and better and the mistakes fewer and fewer, but the fact will remain for a long time: the translation programs do not have a clue about what they are translating, and what the sentences really mean. But the illusion of real intelligence will become more and more convincing, and the risk that we let the machines do what only humans should do will increase if we are not cautious.

Sound research and usage of AI should focus on understanding of how, why, and when the AI systems work and do not work, which is also recognized in recent research efforts in Swedish AI. For example, we need research to find out how the new types of deep neural networks for image analysis really work, and why they distinguish between an image of a car and a real car. In order to safely use such a system, we also need to find the limits for when and under what conditions the system is reliable.

There is also a need to design our robots so that they talk, or otherwise communicate, what they do, and why. So far, most robots are so simple that the need doesn’t exist, but soon they will be considerably more complex, versatile and more difficult to predict. Then they should also be able to explain what they are planning to do, what they want to do, what constraints they have, what they know, what they want to know, and many other things. In short, we must be able to understand the robots in the same way as we understand other people.

A well-designed AI system for assessing loan applications can potentially be less biased than its human colleagues. But this requires more intelligent AI than today’s data driven systems that cannot distinguish between statistical correlations and true causal dependencies. Such truly intelligent systems will probably be developed in the future, but then as now, a wise usage of AI should be governed by an awareness of the systems’ limitations.

DN Debatt.7 oktober 2018

Debattartikel

Thomas Hellström, professor i datavetenskap vid Umeå Universitet:

”Farlig övertro på AI som ännu är allt för ointelligent”

English translation

Thomas Hellström, Professor in Computing Science at Umeå University:

”Dangerous over-confidence in AI that so far is too unintelligent”